Global Epidemiology of Liver Cancer

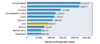

In 2020, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was the seventh most common malignancy worldwide, with approximately 900,00 cases, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death (Figure 1).[1] The rates of liver cancer are highest in Asia and in Notherrn Africa.[1] Among all cases of liver cancer globally, the rates are much higher in males (14.1 per 100,000 people) than in females (5.2 per 100,000 people).[1]

Epidemiology of Liver Cancer in the United States

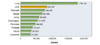

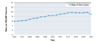

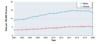

In the United States, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) data for “liver cancer” combines liver and intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma.[2] Liver cancer data for the United States, including trends and demographic features, are shown in (Figure 2) below.[2] The annual reported rate of liver cancer in the United States has changed significantly in the past 30 years. In 1992, the rate of new cases of liver and intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma was 4.46 per 100,000 persons, but this increased steadily to a peak of 9.38 cases per 100,000 persons in 2015, followed by a decrease in recent years.[2,3] In 2023, there were an estimated 41,210 new cases of liver and intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma reported in the United States, accounting for 2.1% of all new cancer cases.[2] The significant increase in HCC incidence in the United States over the past 30 years has been largely attributable to HCV-related HCC.[4] Rates of liver cancer in the United States show major differences based on sex, age, and race/ethnicity.[2] Data from 2000 to 2020 showed rates of liver and intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma in the United States are consistently higher in males than females.[2] Most of the cases of liver and intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma have occurred in persons 55 to 74 years of age, with a median age of 66 years for persons newly diagnosed with liver cancer.[2] There are significant differences in new liver cancer diagnoses based on race/ethnicity, with the highest rates among American Indian/Alaska Natives and Hispanic people.[2] From 2016-2020, liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer was the sixth leading cause of cancer death in the United States, and the median age of those who died was 68 years.[2]